March 1997

Wamboin in the History Books

by Ned Noel

I have been trying to find in any local histories anything about white settlement in this area so as to reproduce it in the Whisper, and haven't come up with much, except the paragraph below quoted in full from Page 14 of Gundaroo, by Errol Lea-Scarlett, 1971 (available at the Queanbeyan and Bungendore Libraries).

"While the scramble for river frontages was taking place in the mature parts of the Yass River there was little interest in purchasing freeholds higher up. William Guise bought a few sections which enabled him to run his flocks, if he wished, on unpurchased land between them, and the only other purchaser in the rough ranges near the source of the Yass River was William Moore. Guise's blocks in the high country were first applied for in 1837 by Stephen Burcher of Liverpool who, although unsuccessful in his bid, is commemorated in "Bircham's Creek" which, with Kowan Creek, forms the source of the Yass River. William Moore of Piper's Hill, Campbelltown, purchased 640 acres at the head of Brooks Creek, on the track from Gundaroo to Bungendore in 1838 and for many years lived quietly but industriously on his property which he named Creekborough. He died there in January 1861 aged 84, and the property was not long afterwards purchased by John Walker."

April 1997

Stories from Wamboin

by Frank Watson

Back in the 1920's, my grandfather Frank Hyles was building up his sheep numbers and land holdings in the Wamboin area. He owned land in central Wamboin that was called Cannings, Merino Vale, Birchmans Gully, Brooks and Leahys.

The best land he owned in the area would have been Old Kowen and Merino Vale. There was a mud hut on Old Kowen about one kilometre south of the intersection of the Yass River and the present location of Norton Road. Even today I have two paddocks I call Mud Hut East and Mud Hut West.

One person who lived in the mud hut was Mr. Flanagan, his wife and child. He worked for my grandfather and wrote him a letter which is reproduced below. It was written in 1925 and unfortunately I have no more information on the Flanagans apart from the letter.

In 1951 the Korean War created a wool boom and my grandfather decided to purchase two Fiat bulldozers. Jack Welch delivered the bulldozers as a salesman for Tutt Bryant. Jack ended up living in Wamboin for 25 years (1951–1976) and being with our family for 38 years, mainly working for my father Peter Watson at Wamboin or Murryong.

Whilst living at Wamboin, Jack Welch built dams, fences, cattle yards and planted crops, pastures, windbreaks and two large forestry plantations for my mother and for Dr. Bruce Shepherd. Each plantation in Wamboin is about 500 acres of radiata pine now being harvested or nearly ready to be harvested.

As you drive from Bungendore to the Wamboin shop on Norton Road (Ed. The shop used to be on the corner of Bingley Way and Norton Road) you can see a yellow farm house in the distance looking south towards Kowen Forest. Jack and Nita Welch raised six children, Peter, Steven, Allen, Gregory, Evelyn and Karen, in Wamboin between 1951 and 1976, and their access was via Kowen Forest to Molonglo Gorge forestry road.

The land off Bingley Way used to be called Cannings. The land from Bingley Way to Weeroona Drive along Norton Road and all the land off Merino Vale Drive was part of Merino Vale. Leahys now belongs to Bruce Shepherd. Brooks is the Norton Road and Ryans Road land and Old Kowen is still with me.

My grandfather Frank Hyles sold 5000 acres of the above land in 1950 and this now forms a larger part of central Wamboin. This land was managed in the 1940’s from Murryong down on the Kings Highway and sheep for shearing would go down to Murryong.

Click here to view an overlay of the Merino Vale subdivision on the present map of Wamboin.

Cannings was purchased by Ernie Armour and run by his son Ian Armour before he sold it to a land developer in about 1972. Ian Armour had good sheep and wool and was also a wool classer. He now lives in Canberra. The Armour’s homestead was on the Sutton Road towards Queanbeyan near Norton Road.

Merino Vale was purchased by the Harriotts in 1950 and then they sold it to the Majors in about 1962. The Harriotts and the Majors improved the pastures near Merino Vale Drive and Norton Road near the Yass River crossing. After they sold Merino Vale, Barney Harriott purchased two small Mercedes livestock trucks. Mrs. Judy Harriott was the sister of Norm Shepherd, famous as a Toyota truck and car dealer in Fyshwick. She was a hard worker on the farm, spreading superphosphate and later driving a big semi-trailer carrying livestock throughout southern NSW.

Birchmans Gully was owned by Bob Denley, a shearer, and his family was based on the Sutton Road, apparently. Also the Bingley family owned Leahys for a while and the Ryan family owned Brooks. The Ryan family relocated to Gundaroo where they have a large grazing property and Bill Ryan junior is a Veterinary Surgeon in Calwell.

The woolshed on Merino Vale was built in the early l970’s for the Majors by Cecil Guy. Cecil worked on Old Kowen, Millpost and Murryong in the 1977-81 period and he was a good horseman, being involved in the Show Society, polocrosse, race club, rodeo, etc. at Bungendore. He later purchased a farm in Summer Hill Road in the Geary’s Gap area.

In the 1970’s the Majors had some Brahman cattle and once a Brahman bull got into our Mud Hut East paddock. According to my diary it was on the 6th October 1977 that a Brahman bull chased Cecil Guy on his stock horse and the bull appeared taller and faster than the horse and rider. Cecil was flat strap to avoid the horns of the bull. That happened near the Yass River and south of the present location of the intersection of Norton Road and Weeroona Drive on a big flat paddock.

In the 1930s some graziers were making more out of rabbits than they were out of wool. My grandfather was trading sheep and he had big mobs of sheep on the road going long distances such as to and from Goulburn or Cooma.

In the l930’s if you were driving down a very steep hill such as Norton Road near Sutton Road you would

need three things—a foot brake, a hand brake, and a tree stump tied to the back.

Back in the 1970’s a bushfire took off in Dr. Shepherd’s after a bulldozer knocked down a tree which brought

down the electricity power line. Jack Welch was driving the dozer and Nita Welch was alone at the house, say two

miles away and she noticed a brown out and then a bushfire going up like an atomic bomb. It was about May, 1975,

and she could not drive or contact Jack and feared he had either been electrocuted or killed in the fire and she raced

over the paddocks towards him. She was at Murryong outstation in Wamboin and he was over near Ryan’s Road.

Fortunately he was safe.

Battling the bushfires, planting pine trees, and raising six children took its toll and his health suffered in the

late l970’s. He left Wamboin and the Welches continued to live over at Murryong until the property was sold in

1989.

In the l970’s Tim Booth and Elaine Wagstaff lived in the cottage on Merino Vale. Tim has been a science

teacher at Queanbeyan High School for many years. I was visiting them one weekend and saw the Majors mustering

their cattle. Bill Major was trotting 100 meters behind the mob on a small grey pony and Mrs. Judy Major was

mustering the mob at high speed in the family Ford Fairlane.

The Bingleys purchased land from my grandfather that now belongs to Bruce Shepherd in the area south of

Ryan’s Road. The Bingleys still own land down on Sutton Road and they are beekeepers, wool growers, and haulage

contractors. They are a large family and I have less information on them.

There are mud huts in the Kowen Forest area, a stone house near Molonglo River, a pise house ruin near

Merino Vale cottage, and a workman’s hut built in the 1930’s on land near Kowen Forest.

In the 1960’s Jack Welch planted oats and wheat on Old Kowen also known as Murryong outstation. A

carrier, Ray Guy, carted a load of wheat out past Majors and over to Mac’s Reef Road via Birchman’s Gully, owned by

Bob Denley at that time.

Before Norton Road was built it took about an hour or more to get to Canberra because you had to travel over

dirt tracks and paddocks opening many gates, going through Birchman’s Gully and Macs Reef Road.

Jack Bish would ride his horse around Old Kowen and Millpost nearly every working day between 1955 and

1977. He would venture onto Wamboin land if our sheep or cattle had escaped. The Shire includes Old Kowen

(Murryong Outstation) as South Wamboin on their planning maps.

In recent years Greg Webb has been working on Old Kowen building a woolshed, electric fences and helping

with stock work. He used to work full time on Lanyon in the I970’s. Now he freelances as a rural fencer and

occasionally works for John Fraser of Merino Vale Drive.

In my diary of 31 July 1975 I have a note saying that Mrs. Judy Major rang Dad at 8:30 am and said she

wanted to subdivide some land. Dad said she could only have access for sub-divisions through the dedicated road on

Old Kowen. This was before Norton Road and when subdivision access was proposed via a road that would come

Molonglo Gorge through Kowen Forest into central Wamboin. My Dad, Peter Watson, did not want to allow this

access route. In the end subdivisions developed from Sutton Road eastwards, and Norton Road grew as they

occurred, starting with the land belonging to the Cartwrights, then the Bingleys, then the Armours, the Majors, and

the Ryans.

In my diary of 3rd May 1977 I said I went over to Old Kowen and got 8 heifers back from Cannings (Bingley

Way). Whilst in there I saw two men working on a tournapull putting in a road for a subdivision. Also I saw two

surveyors planning a road.

People who know about Wamboin back into the 1930s would be Bill Cartwright of Sutton, Jim O’Malley of

Queanbeyan and Ray Colverwell of Queanbeyan.

June 1997

A Bit of the Area’s History

As told by Mr. Bill Cartwright of “Woodbury” on Sutton Road

Compiled by Ned Noel

Mr. Bill Cartwright’s great grandfather settled in this area in 1862. In about 1935 Bill’s father, Jack

Cartwright and his father’s brother, Frank Cartwright, lived in portions of the family grazing property “Woodbury”, in

the area of Sutton Road and Macs Reef Road. Bill Cartwright and his wife Fay still reside there today.

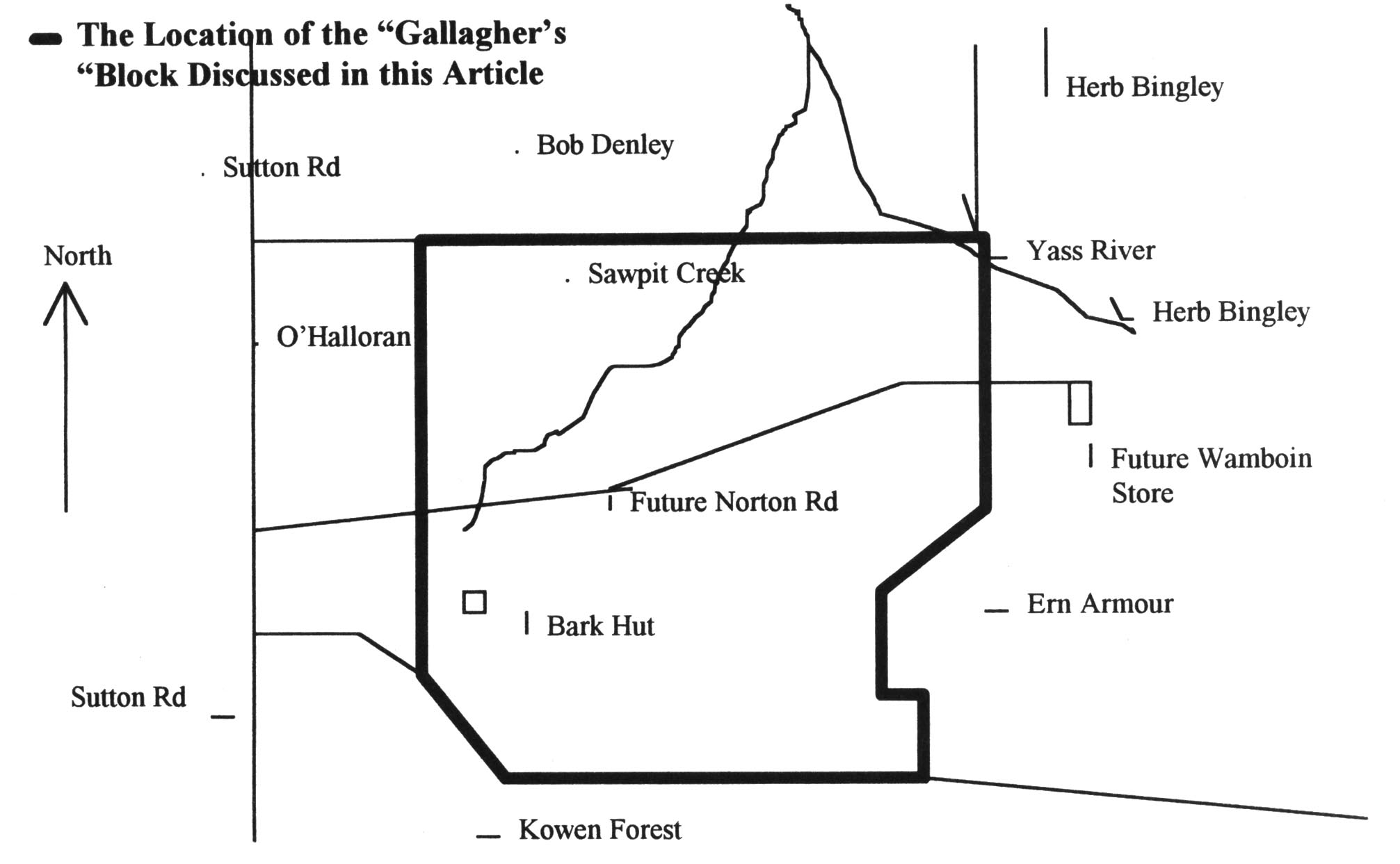

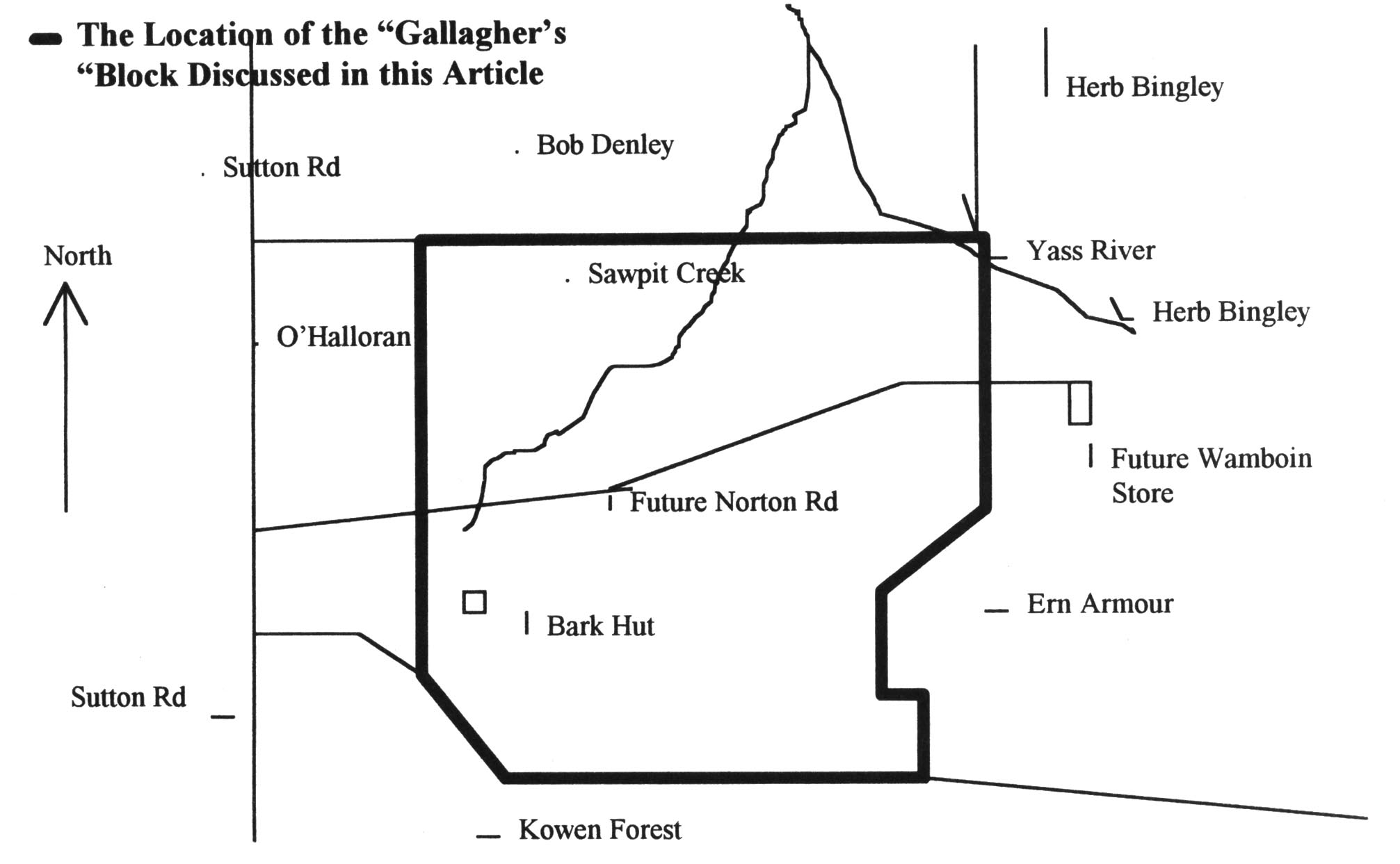

As a way to have an extended area for grazing, the brothers bought 1400 acres of land in the area now

traversed by the western portion of Norton Road. Roughly, the area was a rectangle extending north from Kowen

Forest to a couple miles north of the present Norton Road, bounded on the west by the ridge just east of Sutton road

and extending eastward to about the present Canning Close. The Cartwright brothers were given the money to start

the purchase by their uncle, Jimmy Dunn, who won the Queensland golden lottery prize of £50,000. They

bought the land from Tom Gallagher, a man who had owned it for a long time, perhaps since before 1900. By 1935

he was getting too old to carry on with the work of managing sheep on the land. Some members of the Gallagher

family lived near the Molonglo River crossing on the Kings Highway about 10km west of Bungendore.

The 1400 acres of land they purchased in the Warnboin area was good wool growing land, as it had already

been cleared. It supported 1000 to 1100 wethers.

There is a old building site on the land, now located west of Cooper road and south of Norton Road, called

"The Bark Hut". Only a stone chimney remained in the 1950s. Bill Cartwright remembers camping there for six weeks

in the winter in 1947, with his cousin Jerry and a pack of dogs. They were there to carry out rabbiting and scrubbing.

One night a snow storm came and left six inches of snow.

One problem of the Gallagher’s block was that it was “landlocked”. The Cartwrights could only get into it

“through the grace of others” either by way of the Kowan Forrest Road or through Bob Denley’s property to its north.

Bill remembers that to get the 1000 or so wethers sheared and dipped they had to be nun all the way northward to Bob

Denley’s property, then out onto Sutton Road about halfway between the present Norton Road and the Federal

Highway, then north along Sutton Road to the shearing shed at Woodbury on the east side of Sutton road about two

kilometres south of the Federal Highway.

In the 30s, 40s, and 50s Macs Reef road was a very rough gravel road. It carried only about 20 cars a day.

The road was not fenced, so the sheep roamed on the road and cars stopped for them.

Formerly there was a large property called O’Halloran’s along the east side of Sutton Road from the ACT

border to about the spot of the shearing shed. The shearing shed can also be located as being opposite the Cooper’s

house on the west side of Sutton Road. Mr. O’Halloran owned the property, but a shearer named Glen Smith leased it

from O’Halloran from about 1935 to about 1980. O’Halloran also bought other land close to the ACT boundary,

including large tracts near the present Queanbeyan railway station and at Environa near Hume. Blocks at Environa

were sold to people from as far away as England and South Africa. The property on Sutton Road north of Norton

Road was purchased around 1980 by Athol Morris, a panel beater from Canberra.

The Cartwrights would go onto Gallagher’s, the large Wamboin block, only about once a month to muster or

to build or repair sheep yards. The area was very quiet, with the only sound coming from birds and a few aeroplanes a

day. It was “an isolated area, completely quiet and still.” In the whole area bounded by Sutton Road on the west,

Kowen Forrest on the south, Macs Reef Road on the north, and the Lake George Range on the east, there would only

have been about ten houses well into the 1960s. These included Jack Welch, the bulldozer driver, a couple of houses

on the Watson’s land, Glenn Smith’s house on Sutton Road, 3 or 4 houses on Sutton Road belonging to the Bingleys,

the Cartwrights’ houses, Gordon Bingley near Kowen Forrest on land he bought around 1950 from the Hyles family,

Bob Denley and the Harriots in blocks just south of Macs Reef, and the Riordans in Clare.

The Cartwrights when working their Wamboin (Gallagher’s) block would sometimes run into a saw miller

named Rayner who used to take out logs. There is in the area a creek called Sawpit Creek, flowing northeastward

from the west side of the ridge just east of Sutton Road to the Yass river, meeting it about 6km south of the present

Macs Reef bridge. Timber logs were taken from this area and this may have been the reason for the name of the

creek. Raynor was a saw miller at Queanbeyan and collected logs from Gallaghers. Bill Cartwright doesn’t know

whether Raynor had a sawmill there or not. A short little railway was ported into the bush near the cutting areas to use

for running the logs into a saw operated by Les and Herb Bingley to cut timber for the Cartwrights about 1950.

Various woodcutters took a lot of wood, especially Stringybark and Red Box, out of the area to customers in Canberra

and Queanbcyan. Much of it went to a woodyard near the War Memorial. Some persons involved in woodcutting

were Stan White, who used to live in Sutton, and the Webbers of Queanbcyan. Trees were cut into 6 foot lengths

using axes, with the bigger logs split to make them lighter. In Canberra they were cut down further into fireplace logs.

Bill believes that all of Wamboin, now bare of trees in many places, was once quite forested.

In the 20s, 30s, and 40s the Cartwrights used to allow Sutton residents to get firewood from the parts of

Woodbury closest to Sutton. There was plenty of wood in the area, so this arrangement helped cut fire risk and also

was a way of showing “a bit of community spirit.”

Like most graziers,the Cartwrights removed many trees, as it opened up the land for sheep. At least one of

the local graziers tried to remove all trees. The Cartwrights did not follow this approach. They felt that leaving some

trees was wise. Trees provided protection for the sheep, so that they did not use as much of their energy to keep

warm, needed less feed and stayed in better condition through the winter. Trees also prevented the land from drying

out as fast in hot summer winds, and hence kept the pasture in better condition. Mr. Cartwright’s grandfather paid a

man to ringbark most of the trees in one area, and asking him to leave some untouched for these reasons. The man

later boasted to other people that he had ringbarked every single one.

Mr. Cartwright’s father, Jack Cartwright, died in 1966. His mother and his sisters owned the land, and Bill

Cartwright and his brother worked it for them for about three years until 1969. They then sold it to a developer. The

developer had previously bought the O’Halloran’s block, along the east side of Sutton Road just north of the ACT

border. The two blocks together provided sufficient land for subdivision, the beginning of the new subdivided

Wamboin. Norton Road was started in 1970 or 1971, and extended up the big hill from Sutton Road and a bit further

after passing over the hilltop. Bill Cartwright believes it was always sealed, and he does not believe the shire would

have allowed such a steep road to go in without being sealed.

The Cartwrights knew the Hyles Family and the Watsons, but had little contact with them. “We were Sutton

people and they were Queanbeyan and Bungendore people.” The Hyles would come into the land from the Kowan

Forest or Kings Highway end, and, like the Cartwrights, only occasionally when required for mustering, sheep yard

construction, or other grazier’s work.

Bill Cartwright supports a story from James Bingley about shooting wild pigs in the area. He also remembers

many occasions, especially during the winter, when kangaroos were culled. Kangaroos ate the same grass that the

sheep ate, and hence cut into the graziers’ livelihood. The shoots never killed off all the kangaroos, but kept their

numbers down to about 20% of what they are today. The kangaroos were also deterred then by the absence of water.

Today Mr. Cartwright notes, on a morning plane flight from Canberra to Sydney the area glitters with reflected

sunlight from hundreds of dams, which the kangaroos use for water.

In addition to the Wamboin fire of 1985 Bill remembers the big fire that hit Sutton in 1979. It burned 72,000

acres in 24 hours. It started in Hall when electricity lines touched, and was pushed by northwesterlies to the Sutton

area, where it burned several outlying houses as well as large areas of grass, trees, and fences. Then the wind changed

to a southwesterly, and the fire moved from the Sutton area towards Lake George. On Woodbury, their property just

south of Sutton, the Cartwrights lost about 300 sheep and most of their fencing. "It was a big disturbance in our

lives.”

Bill can also remember a smaller fire that burned around 50 acres around 1948. It was started by a wood

carter boiling a billy beside a dam.

On the Woodbury property Bill also remembers many floods on the Yass River. The property is about a

kilometre above the Macs Reef Road Yass River Bridge. The Cartwrights and their neighbours on the eastern side of the

river, the Rudds, have fences that cross the river to allow stock access, in this pattern:

Floods often took out the fences. The biggest flood Bill can remember was in 1982. As in most of the

floods, the river rose quickly and dropped quickly. Mrs. McGlaughlin, who was living at the Rudds at the time, woke

up in the middle of the night and went into her kitchen and looked out the window. The rain had ended and the sky

had cleared. Mrs. McGlaughlin was amazed to see, lit up by the moon, an enormous body of water between her and

the Cartwrights. The next morning the river had already receded substantially but the line of sticks left by the flood

crest went 200 meters into the Rudds’ land on the east side of the river and 100 meters into the Cartwrights’ land on

the west side of the river.

Bill wonders about the new bridge. Because it is an arched bridge rather than a shallow crossing, in a really

big flood it may act as a dam. It could force water back over his farm and the others just upstream of the bridge. The

really big floods happen very quickly, lasting only 30 minutes to an hour, but in that amount of time the new bridge

could cause considerable damage by damming up the river if there is so much water that it cannot all fit under the

arch.

Bill thinks the Rehwinkles, who ran the animal farm until a couple years ago, bought their land about 20

years ago. The same land was once part of Woodbury, owned by his grandfather and his grandfather’s brother.

Bill has never heard any stories about aborigines in the area. The only accounts he has ever heard about

aborigines deal with the Orroral and Urriara areas now in the ACT.

The Sutton Fire Brigade was officially formed in 1951. Before then firefighting was done by private people,

usually with beaters, and, as time went on, with their own pumps and trucks. Getting help was in some ways easier,

because in those days everyone’s phone was plugged into the Sutton exchange. All the plugs could be plugged in at

once and then all the phones in the area would ring simultaneously to allow the news to be quickly spread. A number

of people could arrive within ten minutes, surround the fire, cut fences where necessary, and follow the line of the fire.

Bill thinks that in many ways the increased population has made firefighting more dangerous. In earlier

times there might be only one house on two thousand acres, and so it could be protected. Now there might be 50 or a

hundred houses on the same amount of land, so a fast moving fire could endanger them much more quickly. It might

be that only 4 or 5 trucks could be available in the first half hour, and l5 or 20 in two hours. He points out that people

should take care to keep grass and brush away from the house, as this increases opportunities for trouble in a fire.

The Cartwrights had always maintained a tip of their own on their land on a little stony knob. The Shire put

in the Macs Reef Tip about 20 years ago. “It’s something that’s got to be.”

All the settlement has in some ways made life more difficult for graziers. Some of the problems that have

increased with settlement are increased numbers of kangaroos, roaming dogs, higher rates, and a greater bushfire risk.

September 1997

A Bit of Wamboin’s History

Provided by Ray Murphy, Bernie Reardon and Tony Reardon

Compiled by Ned Noel

Much of the land just west of the Lake George Escarpment in the Smith’s Gap area was owned in the early l900`s by the Leahy Family. The Leahys' name for their property was Clare. It included the present Clare Valley area, the present Forest Road Area, the present Brooks Creek Estate, and a good bit of the land along Gundaroo Road between Macs Reef Road and the Federal Highway including the present Summer Hill Area. They built a house on Clare in about 1915. They also owned and lived at Elmslea in Bungendore.

Pat Reardon purchased Clare from the Leahys around 1930. Pat Reardon had four sons, Bede, Paul, Frank, and Les, and three daughters, Therese (Girlie), Patricia, and Jean. The land purchased by Pat was divided up for the children. Les Reardon had the southwest portion including Clare Lane and Clare Valley. Les’ portion was about 2200 acres. Bede had the northeast portion, including the present Forest Road area, Paul had the southeast portion, between the escarpment and the present Carinya Park/Clare Lane, including the Highland Valley area. Frank had the northwest portion, including the present Summerhill Road area. Girlie married Trevor Milligan and owned the present Weeroona area which adjoined the Denley property whilst they lived in the ACT. Patricia married Jim Darmody and lived in Bungendore whilst owning land adjoining Weeroona and the Denley property. Jean married Frank Hallam and was given the original Reardon home and property “Lumley” on Macs Reef Road, near the Yass River. Paul Reardon`s portion was purchased in the late l960’s by Les, Moira, and son Tony Reardon, this including the present Highland Valley.

Ray Murphy’s father, Fabian Murphy, in the late l940’s, owned 300 acres including all but the westernmost portion of the area along Norton Road, presently called Yalana. He ran about 600 wethers there. This land was not as rich as that in Clare Valley. To support himself Ray`s father also did contracting, mining, shearing, wood carting, and ran a butcher shop in Bungendore. Ray remembers working in the present Yalana area. They cleared some of the trees and superphosphated some of the land, trying to increase the value of the land for woolgrowing. They would remove trees from some areas but leave them in others. as trees provided valuable protection for the sheep.

The area was good for very fine wool, anything from 16 to 20 microns. Colder, harsher areas tend to produce this very fine wool because the feed is less luscious than on better lands, and the wool is cleaner because there is less dust. This sort of wool has been prized by people like the Italians who use it to make fine wool garments. In the l960’s this very fine wool was worth “a pound a pound". Thicker wool is less valuable. At 24 microns, for example, it is classed as carpet wool.

Ray Murphy started working in the Wamboin area after leaving school at age 14 in 1949. His first job was a two year stint working for Les Reardon. Pat Reardon, Les’s father, used to live at Lumley, on Mac’s Reef Road near the Yass River, but came out to Clare Valley almost every day. Les moved into the Clare house around l938 and was joined by his wife Moira in i942 after their marriage. The house still stands today, just south of Bernie Reardon’s home, “Carinya Park”.

Ray Murphy, in |949-50, did shearing, fencing, and rabbiting for Les. At that time the Reardons were running about 11,000 sheep in the area now roughly covered by Clare Valley, Summerhill, Weeroona, and Damiody’s and Elmslea in Bungendore. Other local graziers such as the Donnellys, Taylors, and Southwells used the Clare woolshed for shearing. Part of the Donnelly property, the present Brooks Creek Estate, was purchased by Les and Moira Reardon in the late l950’s. Donnellys also owned the Creekborough area.

In about 1954 Ray’s father sold his land in the present Yalana to Vic Southwell of Queanbeyan. Ray moved with him and worked in that area for a few years. Vic Southwell then sold the land to the Ryans and moved to the Forbes area.

Ray came back to the Bungendore and Geary’s Gap area in about 1957 when he was 23. He earned his living through shearing and fencing work. In those days the fencing work was done with a crowbar and a shovel, and later on with tractors and kanga hammers.

Ray remembers that while shearing for Bede Reardon in the Forest Road area, a real estate agent approached Bede and proposed subdividing some of that area into 40 acre blocks. This proposal went through and produced one of the first rural residential subdivisions in the area. This was in the early 1970s.

Ray read the article in the April '97 Whisper by Frank Watson. He thinks he knows the identity of M. Flamiigan who in 1925 wrote the letter that was reproduced in that article. He says that a John Flannigan worked for him as a fencer and shearer for many years, and had an extensive knowledge of the Wamboin area. John`s father was Mick Flannigan, and Ray thinks he is probably the author of the letter. John Flannigan is about 70 now. He left this area a number of years ago and then worked for a wool classing outfit in Sydney.

In the l950’s, 60’s, and 70’s there were only three northern entrances into the land just north of the ACT border, presently part of central Wamboin and Yalana. These were the rights of way along Joe Rock’s Road, Clare Lane, and the present Greenway east of Weeroona Drive. The Hyles and Watsons could access their portions of this land by coming in from entrances off the Kings Highway between Kowan Forrest and Bungendore. Landowners were reluctant to permit additional entrances, partly because by law any regular access through a section of land eventually becomes yet another legal right of way. For instance, there was no right of way into the central Wamboin area from Sutton Road until Norton Road was built by developers in about l97l.

Ray Murphy has continued with contract shearing and fencing to this day, and now employs about 16 men during the shearing season. His wife Helen organises the cooking. Her father, Bill Allen, who recently passed away, worked all his life on the land and managed several properties in the Bungendore area.

There are several large flocks in the greater Bungendore Area for which the Murphys generally do the shearing.

Woolcarra and Foxlow on the Captains Flat Road and Currandooley on the Bungendore-Tarago Road each have about l8,000 sheep. Outside the shearing season Ray organises crutching and fencing work. He has also trained and used numerous sheep dogs over the years.

Ray notes the enormous increase in kangaroos in recent years and believes there should be more culling, as the kangaroos cause many car accidents and consume much of the available grass. He says that previously kangaroos were culled, but there was never a desire to eliminate them altogether.

He also remembers spending time rabbiting in his earlier years. The rabbits were a pest because they consumed pasture and dug holes. It was possible to make a living trapping rabbits. Good trappers would set a line of |00 traps. Most of these would catch a rabbit by mid afternoon. They could be emptied and reset to catch another by morning, giving a total of about |50 rabbits per day. Buyers would come in once a month to buy the skins for a cent a skin. Many of the skins went into Akubra hats.

Wild pigs have also been plentiful in the Wamboin/Geary’s Gap area, and Ray Murphy says there are still some around today. He has never heard of any koala sightings in the Wamboin area.

The Majors, in the early l960’s, bought the land in the present Norton Road, Merino Vale Drive area from the Harriotts who lived on Macs Reef Road. Ray Murphy remembers introducing Cecil Guy to them. Cecil built the shearing shed which now sits alongside the old cottage just northwest of the Weeroona Drive/Norton Road intersection. The cottage had already been there for many years by that time. Ray also did the shearing for the Majors, and remembers they had about l800 sheep at Merino Vale. The Majors lived in Canberra, but stayed in the cottage occasionally.

Ray also notes that much of the Wamboin/Geary’s Gap shearing was done in the shearing shed that still stands just south of the intersection of Macs Reef Road and Gundaroo Road (since renamed Bungendore Road). The flocks from the Ryans, the Taylors, the Donnelleys, the Reardons, and from Lumley were brought there.

Ray has watched over the years as subdivisions sprout up on lands previously used for grazing. The money to be made from subdividing often outweighs the ever increasing cost of wool growing, where costs keep increasing in areas like wages, selling costs, drenches, and insurances.

Les Reardon served for many years as a Shire Councillor. In about 1990 he sold the present Clare Valley area to Asset Developments Pty Ltd, who developed the 70 rural residential blocks in the valley.

The Ryans kept the land in the present Yalana and ran stock on it until about 1990. Around that time Bill Ryan bought the westernmost portion of Yalana from the Majors so that he could extend Norton Road eastward from its then terminating point at Weeroona Drive, in the land subdivided by the Majors. This enabled the rural residential development of the Ya|ana area. Eventually the stretch of Norton Road in Yalana was linked at its western end with the stretch of Norton Road for the rural residential development in Clare Valley.

Les Reardon died a few years ago. His wife Moira lives in the area, as do several of his sons and one daughter.

February 2018

Wamboin’s Hidden Hydrological History

by Peter Komidar

Wamboin’s Hidden Hydrological History

Towards the end of last year, my wife and I spent considerable time in the Council Reserve off Bingley Way, scouting old trails for the Kowen Trail Run event. On one of these excursions, I noticed an old track with heavy vehicle tyre ruts. I knew it was old because there were some pretty large trees that had grown in between those tyre ruts. Following the ruts for a few metres, we then discovered a very straight trail – clearly not a kangaroo track. We followed this trail in turn and discovered a star picket with a number placed on the top. More numbered star pickets revealed themselves as we continued along the trail. The trail ended at the top of a stream, so we decided to follow the stream line. After just 30 metres or so, we found blocks of concrete in the ground with orange electrical conduit rising vertically from them. Further down the stream we found a large block of concrete set into the streambed and nearby was a metal weir structure about 1.5 metres high and six metres wide, spanning the stream. On a concrete footing to the weir was the inscription “CSIRO 30/6/1975 Yass 8”.

Clearly, CSIRO was undertaking some form of scientific research in the forest all those years ago – when what is now Wamboin was the back blocks of the Bingley sheep station.

After a couple of phone calls and an email exchange I can report, thanks to Joel Green, CSIRO Records Collection Officer, that the site was run by the Hydrology Group of CSIRO’S Division of Land Use Research as an experimental area for the study of water quality and surface and sub-surface hydrology. A one square mile (250 ha) parcel of land was leased by CSIRO from the local land owner. The lease expired on 31 December 1985.

The site was first used in early 1974, with the control weir and the installation of underground instrument cabling etc. completed in 1976. (You can still see some of the cabling strung up a tree beside the saddle trail that runs from the Bingley Way entrance to Kowen Forest).

There was also a building on-site that was originally used as part of a private experimental venture in the hydroponic production of vegetables, then later used to house recording instruments associated with the CSIRO project. The foundations of that building still exist; on private property, adjacent to the Council Reserve. (I discovered them while exploring what I thought was part of the Council Reserve when I first moved to Wamboin 18 years ago).

Interestingly, the site is still providing surface and sub-surface hydrological information of sorts. As it’s constructed of metal, there is relatively pristine metal above the then water line and rusty metal below; evidence that the weir held considerable water back in the day. Alas, even after the heavy falls in early December 2017, the weir is now capable of holding just a little puddle – so far have groundwater levels fallen with the installation of residential bores in the region.

Also, you will find a number of black plastic pots scattered about the area. My guess is that once CSIRO abandoned the site, an enterprising person decided to use the water then stored in the weir to grow a more legally sketchy kind of cash crop! But that, of course, is only supposition.

If you wish to visit the site, walk up the dirt road off Bingley Way (opposite 241 Bingley Way). Where the dirt road takes a 90-degree left turn, you will see a track on the right heading up the hill. Follow the track until it joins the Saddle Trail and head right towards Kowen Forest for 100 metres where you will find a well-marked trail on your left. 100 metres down that trail you will find the weir. Following the trail further along you will spot the other items I mentioned.

Happy trails!

March 2019

Wamboin’s Wyanga School

by David McDonald

The locality of Wyanga

If you peruse the old 19th century parish maps of Wamboin, you may notice an anomaly: a two-acre block set among the many 40-acre-plus selections in what we know today as Clare Valley. It is the site of the Wyanga school. It lies between Reedy Creek and the track that formerly ran from Queanbeyan north-east to join the Gundaroo Road (what we now call Bungendore Road) immediately south of the Bungendore Road/Macs Reef Road intersection. Today’s Weeroona Drive follows part of that old track. The school site is on private property east of the sharp curve in Weeroona Drive, three kilometres from Norton Road and 2½ kilometres from Denley Drive.

In the 1870s the area was known as Wyanga, despite the parish name ‘Wamboin’ having been assigned in the mid-1860s (McDonald 2018). Lea-Scarlett (1972, p. 7) referred to Wyanga as:

…an isolated and tiny community of struggling selectors in the Lake George Ranges, about twenty miles from Queanbeyan. Although a surveyed road from Bungendore to Gundaroo ran close to the settlement, communications were inconvenient because the pass through Smith’s Gap which today simplifies travel from Bungendore through Wyanga to the modern Federal Highway was not then in existence. With Bungendore only a few miles away, the only link was by horseback or on foot. To the north it was far easier to travel to Gundaroo, about sixteen miles distant, and westward there was a rough track connecting with the busy town of Queanbeyan.

The school site appeared on various maps dating from the earliest parish map (1881) to at least the 1967 County of Murray map where it is shown as ‘WAMBOIN P.S.’ (NSW Dept. of Lands 1967).

In the 1870s, when the school was established, a small number of large land holdings (each of one square mile) were found in the area, though most of what is now Wamboin was small blocks: selectors’ conditional purchases.

Samuel Edmonstone Plumb: the Wyanga school’s first teacher

Plumb was born in Calcutta/Kolkata on 14 Nov 1827. He was a commissioned officer in the 6th Bengal Native Infantry, based in Calcutta, and subsequently emigrated to NSW around 1857 and found employment as a clerk in the GPO, Sydney. He commenced working as a teacher in the Manning River region of NSW in 1859, and while there qualified as a teacher. The following year he commenced teaching at a private school near Cassilis, moved to Muswellbrook in 1866 and later established a private school in the Goulburn area for the children of the people building the railway. He had a reputation for ‘arrogance, snobbishness and irascibility’ (Lea-Scarlett 1972, p. 4) which, along with his propensity for heavy drinking and consumption of tincture of opium, underlay the poor relationships he had with many of the communities within which he lived and worked.

Plumb departed the community of railway gangers under a cloud, and found his way to Wyanga in early 1870. Lea-Scarlett points out that

The principal families [in Wyanga] with children of school age in 1870 were John Lee, Thomas and William Smith (who were Anglicans), Edward Murphy, Michael Byrnes, Bernard Cunningham and John Walker (who were Roman Catholics). There were fourteen Church of England children and twenty-one Catholics, all apparently living in harmony. (op. cit., p. 7)

The descendants of some of these families still live in the Bungendore area, and are active contributors to the Bungendore History Facebook Group.

Plumb found Wyanga to be virgin territory for a school teacher, writing that:

The Lake George Ranges consist of wild hilly country through which there is no mail communication. On visiting the place (which I was induced to do at first from hearing of the beauty of its mountain scenery) I found on it a scattered body of free-selectors, almost all wholly illiterate, with children growing into men & women in utter ignorance. My proposals for a school found favour with them (quoted by Lea-Scarlett, loc. cit.).

Lea-Scarlett explains that Plumb’s ‘…time at Wyanga was his most prolific period as a writer and the result is that from his pen came the only descriptions of the locality in those times and some careful analyses of social conditions’ (loc. cit.).

The school was built in early 1870 as a slab and bark hut measuring 30 feet by 15 feet, with a small room attached in which the teacher lived. At the time of writing his 1972 Memorial Lecture, Lea-Scarlett noted that the building ‘…is still in existence, although now more deservedly used as a shed on the farm of Mr Patrick Mathews at Turalla Reserve, Bungendore’ (op. cit., p. 8). His paper includes a photograph of the shed as reconstructed there. It still stands on the property ‘Turallo Reserve’, visible from Mathews Lane.

Plumb (an Anglican) found himself in the midst of bitter conflict between the Roman Catholic and Anglican selectors in Wyanga, and his own behaviour (including his heavy drinking) exacerbated conflicts he had with the local selectors and with the Catholic hierarchy.

The school opened as a private school in early 1870, though later in the year it became non-viable as the Catholic pupils were withdrawn by their parents. The only pupils remaining were those of John Lee and Thomas Smith, and those men provided some financial support to Plumb as their private teacher.

In early 1871 a Provisional School was established in the single building that then existed in Sutton, a weatherboard building used as a Wesleyan chapel that had been moved there from the Mac’s Reef goldfield once the village of Newington was dismantled. Plumb was appointed as the teacher there, with some sources (e.g. Gillespie 1999) stating that the Sutton and Wyanga schools were half-time schools, with Plumb attending them on alternate days. Conflict and chaos reigned, however, with Plumb’s appointment to the Sutton school ending in September 1871. He again became a private tutor to Smith’s and Lee’s children as there were not enough pupils for the Wyanga school to be viable as a Provisional or Public school.

In August 1872 the Dept of Education recognised it as a Provisional School, with the teacher being Mrs Mary Whyte, the daughter of selector Edward Murphy—she had no teacher training. By this time Plumb had left Wyanga.

The school closed, never to re-open, in December 1874. In the same year the land surrounding the school site was selected by Michael Byrnes, as can be seen on the early maps, though the school site remained excised from the selection.

Today

As you walk, ride or drive along Weeroona Drive, at 3 km from Norton Road and 2½ km from Denley Drive, look to the east, down towards Reedy Creek, and think of the selectors’ children walking, or perhaps riding their horses, to Wamboin’s Wyanga school, some 150 years ago. I do!

Teachers

Samuel Elphinstone (sic) Plumb: August 1871 to May 1872; Mrs Mary White (Lea-Scarlett spelled it ‘Whyte’): June 1872 to July 1872; Mrs Mary Anne (Lea-Scarlett spelled it ‘Ann’) White: August 1872 to December 1874. Source: Gillespie 1999. Note that some of these details differ from those provided in Lea-Scarlett 1972.

Sources and further reading

Much of this article draws on Lea-Scarlett, EJ 1972, ‘Magnum Bonum Plumb--terror of the Australian bush. A study of the teaching career of Samuel Edmonstone Plumb’, Descent, vol.6, pt.1, T. D. Mutch Memorial Lecture, read before the Society of Australian Genealogists, 17 August 1972, pp.3-29. Parts of the Lecture’s content is summarised in Lea-Scarlett, EJ 1972, Gundaroo, Roebuck Society Publication no.10, Roebuck Society, Canberra, pp.68-9.

Gillespie, LL 1999, Early education and schools in the Canberra region: a history of early education in the region, The Wizard Canberra Local History Series, L. Gillespie, Campbell, ACT

Lord, R 1996, Sutton Public School: 125 years of education: 1871-1996, Sutton Public School, Sutton, NSW.

McDonald, D 2018, ‘The parish of Wamboin: its creation and the parish map’, The Whisper, November 2018, p.20.

New South Wales, Department of Lands 1967, Map of the County of Murray [cartographic material]: Eastern Division, NSW compiled, drawn & printed at the Department of Lands, Sydney, NSW, Dept. of Lands, Sydney.

Appendix 1

The origin of the name ‘Wyanga’

‘Wyanga’ is almost certainly an Aboriginal word. Sutlor (1909) recorded that ‘wyanga’ is from the Port Jackson language, meaning ‘mother’. This is reflected in one of Australia’s most respected Aboriginal community-controlled health services, the Redfern-based Wyanga Aboriginal Aged Care. They refer to ‘Wyanga (Earth) Malu (Mother)’ and ‘Wyanga: “Mother – the core of Aboriginal people’s spirit”‘. Various dictionaries of Aboriginal words, published after Sutlor’s piece, also refer to ‘wyanga’ meaning ‘mother’ in the Port Jackson language (e.g. Thorpe 1921).

Also in Sydney is the Aboriginal cultural tour company Wyanga Malu, which they translate as ‘Earth Mother’.

Wyanga is also a rural locality and railway station in central NSW on the Parkes-Narromine railway line, 26 km south-west of Narromine. This location is in the traditional country of the Wiradjuri people, and we note that one of the two founders of Redfern’s Wyanga Aboriginal Aged Care, Sylvia Scott, is a Wiradjuri Elder from Cowra, NSW (http://wyanga.org.au/our-historystory).

There are a number of places called Wyangan in and around Griffith, NSW, and others called Wyangala, e.g. Wyangala Dam and village on the Lachlan River near Cowra, and Wyangala National Park, also in the upper Lachlan. And note Wyangala parish in the Boorowa (Hilltops, since the 2016 NSW Council amalgamations) LGA.

In addition, across eastern Australia are found many businesses, roads, properties, etc., called Wyanga, including a pastoral property in central Queensland near Tambo, and a winery in Gippsland.

References for Appendix 1

Sutlor, JB 1909, ‘Aboriginal place names. Vocabularies by J. B. Sutlor, of Bathurst’, Science of Man and Journal of the Royal Anthropological Society of Australasia, vol.11, no.8, pp.160.

Thorpe, WW 1921, List of New South Wales aboriginal place names and their meanings, Australian Museum, Sydney.

Appendix 2

The locality of Wyanga, and the families whose children attended Wyanga school

I am not aware of any published account of the boundaries of Wyanga during the period when the locality name was commonly used. Based on Lea-Scarlett’s naming of the families whose children were candidates for the Wyanga school, and the locations of their selections relative to the school site (detailed below), it seems reasonable to suggest that the rough boundaries may have been the Lake George Range to the south and east, the middle of the current Bywong parish to the north, and the vicinity of Merino Vale Drive to the west. Such boundaries are less than five kilometres in a direct line from the school, a not-unreasonable distance for the pupils to travel.

The earliest land acquisitions in the area were by William Moore and William Guise, in 1838. Moore purchased a one square mile (640 acre) block that he named ‘Creekborough’. Its south-western corner straddled the current Bungendore Road/Macs reef Road intersection. Note the current Creekborough Road named after his property. Also in 1838, William Guise, proprietor of ‘Bywong’ station in the Sutton/Gundaroo area, purchased (at auction) two abutting one-square-mile portions of land on Kowan Gully (Kowen Creek), south and west of the current Wirreanda Road. James (and his brother John?) Anlezark also had a 640 acre block. This was on Brooks Creek just north of the top of Smiths Gap; the Forest Road/Forest Lane intersection was the north-eastern corner of his block. James Anlezark is said to have purchased it in 1837 (Aubrey & Jenner 2011). The selectors moved in following the passage of the Crown Land Acts in 1861.

The earliest published mention of ‘Wyanga’ that I have found is the NSW Government Gazette of Saturday 31 Oct 1868 [Issue No. 271 (Supplement)], p.3815: Registration of Brands Act of 1866, Brands Branch, Registrar General’s Office: ‘Third list of cattle brands—third notification: … Wm. Smith, Wyango, Bungendore’. Lea-Scarlett identified William Smith as being one of the selectors in the area in 1870 (see above) and Smiths Gap is named after one of the two William Smiths (father and son) who lived in Wyanga, probably William John Smith (1824–1896).

The next mention was in the NSW Government Gazette dated 10 April 1879, a notice of a horse having been impounded ‘from Wyanga, by John Lee’.

The Bungendore cemetery index includes Catherine Sparrow née Lee, birthplace ‘Wyanga, near Bungendore’, died 04 Apr 1899 at Bungendore, aged 35 years, father John Lee, mother Mary Jane Harriott. Catherine Lee would have been born at Wyanga c. 1864.

In Bert Sheedy’s 1971 interview of Pat Mathews (‘Turalla Reserve’, Mathews Lane, Bungendore), Sheedy mentioned Wyanga twice, albeit very briefly, as if it was (to him and Mathews) a familiar name for that locality. See the 9 minutes 0 seconds point in Session 1, and 26 minutes 50 seconds in Session 2.

Families who undertook to send children to Wyanga school in April 1872

Source of the names: Gillespie 1999, p. 69.

William Smith

Selections in SE corner of Bywong parish immediately east of Creekborough (William Moore) and north of John Anlezark’s block (Wm Smith ACPs 1873, 1874, 1882)

Other Smiths there as well, including Thomas Smith and TW Smith. Smiths Gap was named after a William Smith.

Joseph McEnally

I cannot find any blocks in his name within a few miles of the school.

Bernard Cunningham

Blocks on the eastern side of Brooks Creek between it and the escarpment, Bywong Parish, CP 1864, ACPs 1873 1874 1875, 1879, 1881, 1882 and 1890, about 3 miles NE of Wyanga school.

John Walker

Selections immediately north of Lee’s, i.e. in the triangle of Macs Reef Road and the (Weeroona area) crown road. Also immediately NE of Moore’s ‘Creekborough’. CPs 1880 & 1881 (J Walker), ACP 1888 (J. Walker Jr).

Purchased ‘Creekborough’ from William Moore.

Walker was from County Kildare. His brother James married a girl who was a Souper. In Ireland, these were Catholics who, if they renounced their faith they were given a bowl of soup and automatically became Church of England. At the time of the 1804 Fenian uprising John Walker was said to have informed on the (Catholic) rebels. Three men were appointed by the Fenian Brotherhood to follow Walker to Australia and kill him which they did during a wallaby hunt on ‘Bolero’ station (near Adaminaby). It is believed that McCoy (squatter at Wanniassa) come out to Australia first and may have brought the information about James Walker being a traitor. Because of this family experience, John Walker never went outside his house with unless he was carrying a double-barrelled shotgun. Source: Lea-Scarlett 1972.

Edward Murphy

Cannon (2015) states that he received the first land grant in the parish of Wamboin, 33 acres, 10 Sep 1857 (well before the parish was created). See his block, parish no. 9, 30 acres, the top-right-hand corner touches Bungendore Road at the northern parish boundary, one mile north of the Wyanga school.

Also blocks south of upper Yass River/Cohen Creek, including CP 1879, ACPs 1881, 2 miles from the school (i.e., the current Merino Vale Drive area). Obviously, this was not the first land grant in the parish of Wamboin depending, though, on what definition of a land grant and of the parish of Wamboin one uses.

John Lee

See above, and William Lee and HH Lee

Michael Byrnes (‘Byrne’ on the parish map)

The school block is on one of his selections, 1874. His other nearby blocks were selected in 1870 and 1875, and he had a land grant (?) of 47-3/4 acres straddling the creek immediately north of the block which surrounded the school.

Thomas Smith (brother of William Smith?)

Thomas Smith had many selections on and close to Brooks Creek, near the Lees, south to the parish border, about 2 miles from the Wyanga school.

References for Appendix 2

Aubrey, K & Jenner, K 2011, The story of John Anlezark & Mary Anne Doyle 1812-1889, the authors, Hazelbrook, NSW.

Cannon, Geoff (compiler) & Department of Land and Water Conservation New South Wales (issuing body) 2015, The first title holders of land in the County of Murray, the author, Green Hills, NSW.

Gillespie, LL 1999, Early education and schools in the Canberra region: a history of early education in the region, The Wizard Canberra Local History Series, L. Gillespie, Campbell, ACT.

Lea-Scarlett, EJ 1972, ‘Magnum Bonum Plumb--terror of the Australian bush. A study of the teaching career of Samuel Edmonstone Plumb’, Descent, vol. 6, pt. 1, T. D. Mutch Memorial Lecture, read before the Society of Australian Genealogists, 17 August 1972, pp.3-29. Parts of the Lecture’s content is summarised in Lea-Scarlett, EJ 1972, Gundaroo, Roebuck Society Publication no. 10, Roebuck Society, Canberra, pp.68-9.

Mathews, P 1971, Pat Mathews interviewed by Bert Sheedy for the Bert Sheedy and Marj Sheedy oral history collection [sound recording], recorded 16 January 1971, at ‘Turalla Reserve’, NSW.

August 2019

Trooper Thomas Anlezark

by David McDonald

In the early days of the NSW colony, many of the convicts were political prisoners: Irish men who had been sentenced to transportation to the colony because of their roles in attempting to free Ireland from the oppressive British occupiers of their homeland. That’s a fact, but did you learn, in school, about the Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804? In brief, as the National Museum of Australia puts it:

The Castle Hill Rebellion or ‘Australia’s Vinegar Hill’ began on 4 March 1804. Rebel leaders — Irishmen Philip Cunningham (a veteran of the 1798 rebellion [in Ireland]) and William Johnston — aimed to overtake Parramatta and Port Jackson (Sydney), establish Irish rule and return willing convicts to Ireland.

The plan involved joining with around 1000 other convicts planning to escape from the Hawkesbury region before moving on the settlements. ‘Death or Liberty’ was adopted by the rebels as their rallying call…

Alerted to the rebellion late in the evening, New South Wales Governor Philip Gidley King declared martial law and Major George Johnston of the New South Wales Corps organised troops and civilian volunteers from the Sydney settlement to pursue the convicts. Government forces undertook a forced march through the night until they came within a few kilometres of the rebels.

Riding ahead while the main group continued on foot, Major Johnston, trooper Thomas Anlezark and Father Dixon (a Catholic priest) attempted to convince the rebels to surrender. They met with the response: ‘death or liberty, and a ship to take us home’.

When Johnston approached the convict leaders a second time, he and Trooper Anlezark took advantage of surprise caused by the sudden appearance of government troops and captured Cunningham and another rebel leader.

While retreating with Cunningham, Major Johnston ordered government forces to fire on the convicts: 15 were killed, the others scattering into the bush. At least 15 more convicts were killed in ongoing pursuits, and the majority surrendered or were recaptured.

We now focus on Trooper Thomas Anlezark. You have probably seen the famous painting of the rebellion. Anlezark is mounted, next to Major Johnston, and dressed in a blue military uniform. Anlezark—numerous spellings of the name exist—is an old family name derived from a place in Lancashire called Anglezarke. It is believed to be an old Norse word. Thomas was born in the UK, served as a soldier in the British army, was convicted of burglary, sentenced to death, and the sentence was commuted to transportation. He arrived at Sydney in 1802, and quickly changed his status from a common convict to a member of the military. He lived in Liverpool for most of his time in the colony, dying there in 1834. Thomas Anlezark and his convict wife Ann Starmer had six children while living in Liverpool, the first being James Anlezark, born 1808, and the second John, born in 1812.

On 12 April 1837, James Anlezark purchased land at the top of Smiths Gap—one of the first land purchases in the Wamboin/Bywong area. It was one square mile in area (640 acres) and cost £160. The north-east corner of the block is the junction of the current The Forest Road and Forest Lane, which means that the property straddled the track that became the Gundaroo-Bungendore Road, and that we now call Bungendore Road.

Immediately after purchasing it, James Anlezark sold his block to John Smith (born 1776 in the UK, arrived Sydney as a convict in 1810, settled at Liverpool with his first wife Jane Falkland (many different spellings of her name exist)). It seems to have been a gentlemen’s agreement, as no conveyancing documents recorded the sale. The Smith family moved to our area in 1829, settling at Creekborough (Bywong). Apparently, their first-born daughter, Elizabeth Jane Smith (born Liverpool 1813) stayed behind, as she married James Anlezark in Liverpool in 1830 (and died there at a young age in 1837).

On 8 May 1837, just weeks after Anlezark purchased the block and sold it on to John Smith, Smith sold the southern 250 acres (Bungendore Road is roughly its northern boundary) to William Lee. The Smith and Lee families remained prominent settlers in the area through the subsequent generations.

So, there is the link between the Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804, and the Wamboin/Bywong area: James Anlezark, who purchased the block at the top of Smith’s Gap, was the son of Trooper Thomas Anlezark who played such a prominent role in putting down the rebellion. And Smith’s Gap is said to be named after John Smith’s son William John Smith, born 1824 in Liverpool, died 1896, and buried in Bungendore.

Notes

The first four editions of the Parish of Wamboin map incorrectly show John Anlezark as the purchaser of the block discussed here. The fifth edition, 1927, correctly shows James Anlezark as the first purchaser. I have seen the 1837 conveyancing documents that confirm this.

The information about James/John Anlezark’s Bungendore region landholding is incorrect in Aubrey, K & Jenner, K 2011, The story of John Anlezark & Mary Anne Doyle 1812-1889, the authors, Hazelbrook, NSW.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Stephen Moore, who first alerted me to the Anlezark/Castle Hill Rebellion links. And to Greg Lee, who generously shared with me the results of his family history research, especially regarding land conveyancing in the area settled by the Lee and Smith families.

References

Anlezark, T & Carmody, C 1988, The Anlezarks, the authors, Penshurst, NSW. (The information in this source about the block at the top of Smiths Gap is wrong.)

Brownlow, R & Jones, M c. 2012, Descendants of John Smith, www.gundaroo.info/genealogy/other/johnsmith.doc.

McDonald, D 2019, ‘Smiths Gap: its history and naming’, The Whisper, July 2019, p. 22.

National Museum of Australia, Castle Hill Rebellion, www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/castle-hill-rebellion.

Whitaker, A-M 2009, Castle Hill convict rebellion 1804, The Dictionary of Sydney.

August 2019

Smiths Gap

by David McDonald

Introduction

In the early days of European settlement of the Wamboin/Bywong area (characterised as the wild country in the ranges at the head of Brooks Creek) which commenced in earnest in the 1860s once people were permitted to occupy unsurveyed land by means of conditional purchases (i.e. by selection), there was no route for wheeled vehicles from our area down into Bungendore:

Although a surveyed road from Bungendore to Gundaroo ran close to the settlement, communications were inconvenient because the pass through Smith’s (sic) Gap which today simplifies travel from Bungendore through Wyanga [i.e. the south-eastern part of Wamboin] to the modern Federal Highway was not then in existence. With Bungendore only a few miles away, the only link was by horseback or on foot. To the north it was far easier to travel to Gundaroo, about sixteen miles distant, and westward there was a rough track connecting with the busy town of Queanbeyan (Lea-Scarlett 1972, p.7).

I am sure that all would agree that Smiths Gap is a prominent geographical feature: a gap in the Lake George Range through which Bungendore Road runs. It is a point where three different fault lines intersect on the edge of the Range. The current road cutting reveals the complicated folding of the gap’s ancient sedimentary rocks: Ordovician turbidites of the Pittman Formation, deposited in the deep ocean to the east of the Gondwana super-continent, 460-444 million years ago (Finlayson 2008). It is the only gap in the Lake George Range, through which a public road runs, between Gearys Gap and the ACT border.

Although we do not know the Aboriginal name for the gap, there would certainly have been an Aboriginal walking track through it, providing a route from the headwaters of Brooks Creek down to the highly productive Lake George plain.

Early records of the name ‘Smiths Gap’

The first record that I have found of the use of the name ‘Smiths Gap’ is in the New South Wales Government Gazette of 7 May 1867, page 1144:

BUNGENDORE.—Impounded at Bungendore, on the 3rd day of May, 1867, from Smith’s Gap: damages, 1s.:—One red snail-horned bullock, top off both ears, white spots on both flanks, small white spot in forehead, illegible brand off rump, like blotch brand or whip mark near rump. If not released, will be sold according to Impounding Act. J. WILLIAMS, Poundkeeper. 2270 Is.

In 1870 the colonial government had the first road constructed through the gap, although it was on a different alignment from the current road: Queanbeyan Age, 18 August 1870, page 3:

Tenders Wanted FOR the CUTTING and FORMING of the ROAD known as SMITH’S GAP, near Bungendore. Plan and specification can be seen at Mr. McMahon’s, Bungendore; or, at Mr Donnelly’s, Bywong Gundaroo. Tenders to be opened at noon on the 20th August at Mr Leahy’s, Gundaroo. Trustees. ALEX. McCLUNG J. McMAHON P. B. DONNELLY

The completion of a road through the gap greatly facilitated transportation between Bungendore and Gundaroo. The road was known as Gundaroo Road. The name was changed to Bungendore Road in recent decades because (I am advised by an informant who has lived in the local area for many years) the name duplicated that of the nearby, pre-existing, Gundaroo Road that connects Sutton, Gundaroo and Gunning.

Apparently, the design of the road through the gap did not have traveller safety as a prominent consideration: Goulburn Herald and Chronicle, 13 November 1878, page 4:

BUNGENDORE...On Thursday last Mr. David Gordon, in company with his sister and her two children, were proceeding on their way from here [Bungendore] to Top Flat, and when about half-way up the hill the horse suddenly refused to pull, the consequence being that the cart ran backward, and before Mr. Gordon had time to jump out it was capsized over the edge of the cutting into the gully. How they escaped instant death seems marvellous, as they were all under the cart, which had fallen some six feet over the edge of the cutting. With great difficulty Mr. Gordon succeeded in extricating himself, and at once set to work to free his sister and the children from their perilous position. This he effected by getting on the upper side and giving the cart another turn down the hill. He fully expected to find them dead, as he had also a bag of flour and one of sugar in the cart; but I am glad to state that beyond receiving a severe shaking they are but little worse for the mis hap. This piece of road is in a most dangerous condition and should certainly be made more secure or some lives will be lost. About two years since a dray loaded with wheat went over within a few yards of the same spot. I should strongly advise the in habitants of that part of our district to call a meeting and urge upon the authorities the necessity of erecting a substantial fence throughout the whole length of the cutting. It would not cost a great sum, and might be the means of saving life.

‘Top Flat’, their destination, was the area where Thomas William Smiths’ selections were located some two miles south-west of the gap. David Gordon’s daughter, Janet Smith, lived there. The Gordon family came from Rossi.

A decade later another mishap occurred in the gap, as reported in the Goulburn Herald, 14 August 1888, page 3:

Mr. B. Leahy and Mr. Hayes met with an accident coming down Smith’s Gap on Thursday last. Just as they were about a hundred yards down the hill in the steepest part the horse they had began kicking. Mr. Leahy, who was driving, ran the horse into the bank of the cutting. The buggy capsized and threw both occupants out. The horse managed to get clear of the buggy and bolted down the hill. Beyond a good shaking neither of the occupants was hurt. August 12.

‘Mr B. Leahy’ is probably Blenner Patrick Leahy who had selections at the top of the range and other parts of the parishes of Wamboin and Bywong. The Leahy family took up many selections in our area and, in subsequent years, consolidated them and others to establish the ‘Clare’ property, with its homestead on what is now Clare Lane. ‘Mr. Hayes’ was probably William John Harwood Hayes, the Post and Telegraph Master at Bungendore 1886-1888.

Who was the Smith after whom the gap is named?

The ‘Smith’ after whom the gap appears to be named is William John Smith: Goulburn Evening Penny Post, 10 June 1916, page 5, my emphasis:

Mrs. Ellen Jane Smith, a very old resident, died at her son’s residence on Wednesday morning. The old lady was 93 years of age and had been ailing for some time. Her husband, Mr. William Smith, predeceased her by very many years, and was one of the early settlers over the range on the Bungendore-Gundaroo road. The steep hill was called Smith’s Gap after the late Mr. Smith. Mr. and Mrs. Smith left a large family and numerous relations around this part. The remains were interred in the C.E. Cemetery on Thursday afternoon, and were followed to the grave by a large gathering.

William John Smith was born in 1824 in Liverpool, NSW, and died at Bungendore in 1896, where he was buried in an unmarked grave. Both his parents were convicts. It is reported his parents and their children moved from Sydney to Creekborough (Bywong) in 1829 (Brownlow & Jones c. 2012, Proctor 2001). William John Smith married Ellen Jane McEnally (1823-1916) in 1846 in Braidwood. He took up selections in the Creekborough area, approximately two miles north-west of the top of Smiths Gap, in the 1870s and 1880s.

James Anlezark purchased land at the top of Smiths Gap on 12 April 1837—one of the first land purchases in the Wamboin/Bywong area. It was one square mile in area (640 acres) and cost £160. The north-east corner of the block is the junction of the current The Forest Road and Forest Lane, which means that the property straddled the track that became the Gundaroo-Bungendore Road, and that we now call Bungendore Road. (The early editions of the Wamboin parish map incorrectly show that the land was originally purchased by John Anlezark, the younger brother of James Anlezark.)

Immediately after purchasing it, James Anlezark sold his block to the father of William John Smith, namely John Smith who was born in 1776 in the UK, arrived Sydney as a convict in 1810, and settled at Liverpool with his first wife Jane Falkland (many different spellings of her name exist). The sale of the land seems to have been a gentlemen’s agreement, as no conveyancing documents recorded the sale. As noted above, apparently the Smith family moved to our area in 1829, settling at Creekborough (Bywong).

On 8 May 1837, just weeks after Anlezark purchased the block and sold it to John Smith, Smith sold the southern 250 acres (Bungendore Road is roughly its northern boundary) to William Lee. When John Smith died in Bungendore in 1847, his land was inherited by his son William John Smith, after whom it is believed that the gap is named. The Smith and Lee families remained prominent settlers in the area through the subsequent generations.

Subsequent development of the Gundaroo Road through Smiths Gap

The first edition of the Wamboin parish map, published in 1881, clearly shows the zig-zag of the track through gap on the Gundaroo Road, although the gap is not named on the map.

By the early 1890s the road through the gap was of high enough standard to be used for the regular conveyance of the mail. A Government notice in the Sydney Morning Herald, published on 24 October 1891, reads ‘It is hereby notified that the following Tenders, for the Conveyance of Mails from 1st January next, have been ACCEPTED...Southern roads ... Bungendore and Upper Gundaroo, via Creekborough, Gum-tree Flat, and Brooks Creek, twice a week.’ (Upper Gundaroo was the locality where Shingle Hill Road—the northern continuation of Bungendore Road—crosses the Yass River.)

On 28 July 1896, the Goulburn Evening Penny Post reported ‘In reply to a letter from Mr. O'Sullivan urging repairs to road Bungendore to Gundaroo, at Smith’s Gap, the Under-Secretary replies that tenders have been invited for fencing portions of this road’. Five years later (21 May 1901) the Queanbeyan Observer reported on the deliberations of the committee of the Bungendore Progress Association: ‘Mr. Hanford called attention to the necessity for a fence on the road at Smith’s Gap’. Apparently the lobbying efforts were successful, with the 1902 annual report of the Bungendore Progress Committee listing as, among its achievements over the year, a ‘new fence erected on hill at Smith’s Gap’ (Queanbeyan Observer, 5 August 1902).

The current alignment of the road through the gap differs from the original one. The Queanbeyan Age, 26 Sep 1905, refers to correspondence from the Public Works Department, responding to lobbying by the Bungendore Progress Committee, ‘urging deviation of the Bungendore Upper Gundaroo road at Smith’s gap. It is reported that the section of the existing road, at the place referred to, is now in good condition. The traffic in no way warrants any heavy expenditure on same.’ However, The Age was able to report the following year (28 Dec 1906) that ‘The tender of Mr. J. Walsh has been accepted for the new road at Smith’s Gap. The completion of this work will be a great relief to the members of the Progress Association who have been fighting for the last two years to get it put in hand’. All was not plain sailing, however, as the person who owned the block in which Smiths Gap was found, Nathaniel Powell from ‘Turalla’, ‘will not allow the new road to be opened until it is fenced off by the Government, quite right, but the tenders should have been called and the work progress in whilst the road was being formed’ (Queanbeyan Leader, 8 Mar 1907). The Government Gazette of 20 Mar 1907 notified the ‘Description of Road to be opened:—Deviation in part of road from Gundaroo to Bungendore at Smith’s Gap, parish of Wamboin, county of Murray, Yarrowluma Shire No. 107’. It was confirmed in the Gazette dated 24 December 1907.

Pat Mathews from ‘Turalla Reserve’ on Mathews Lane, Bungendore, interviewed by Bert Sheedy in 1971, discusses the alignment of the road through the gap, comparing the original alignment with that current in 1971.

2002 was the year in which further improvements to the road were completed. Gary Nairn MP, federal Member for Eden-Monaro, issued a media release ‘Road Black Spot Program--improving road safety’. It includes advice that, ‘In Yarrowlumla, there has been realignment along Gundaroo Road halfway up Smiths Gap’ (16 May 2002).

Entering ‘Smiths Gap’ into the Register of the Geographic Names Board of NSW

Despite the community at large, and Council in official documents and signage, referring to the feature as ‘Smiths Gap’, the Geographical Names Board of NSW (GNB) advised that ‘Smiths Gap’ had never been registered as an official Geographical Name. In October 2018 I approached QPRC staff, requesting that they support my proposal to have the GNB register the name, and at its meeting on 22 May 2019, the Queanbeyan-Palerang Regional Council resolved to initiate the naming process.

The proposal was advertised for a month over August/September 2019 and, at the conclusion of that period, the name ‘Smiths Gap’ was assigned in terms of the Geographical Names Act 1966 (NSW). This was notified in the NSW Government Gazette No. 110 of 27 September 2019, pp. 4212-3.

The Geographical Names Board notification is available online. It states:

Description: The gap is located on Bungendore Road, approximately 5kms north-west of the village of Bungendore.

Origin: Known locally as ‘Smiths Gap’ since at least the 1860s. Named after a local family who lived in the area.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Greg Lee, who generously shared with me the results of his family history research, especially regarding land conveyancing in the area settled by the Lee and Smith families.

References

Brownlow, R & Jones, M c. 2012, Descendants of John Smith, Graeme Challinor’s Genealogy Pages, Gundaroo, NSW.

Finlayson, D. M. (compiler) 2008, A geological guide to Canberra region and Namadgi National Park, Geological Society of Australia (ACT Division), Canberra.

Lea-Scarlett, E 1972, ‘Magnum Bonum Plumb—terror of the Australian bush. A study of the teaching career of Samuel Edmonstone Plumb’, Descent, vol.6, pt. 1, T. D. Mutch Memorial Lecture, read before the Society of Australian Genealogists, 17 August 1972, pp.3-29.

Mathews, P 1971, Pat Mathews interviewed by Bert Sheedy for the Bert Sheedy and Marj Sheedy oral history collection [sound recording], recorded 16 January 1971, at ‘Turalla Reserve’, N.S.W.

Procter, P (ed.) 2001, Biographical register of Canberra and Queanbeyan: from the district to the Australian Capital Territory 1820-1930: with Bungendore, Captains Flat, Michelago, Tharwa, Uriarra, Hall, Gundaroo, Gunning, Collector and Tarago, The Heraldry & Genealogy Society of Canberra, Canberra (A.C.T.).

December 2019

Lake George Range

by David McDonald

Samuel Plumb and John Lee take a walk to the

Lake George Range, 1872

Wamboin’s Wyanga School (see March 2019 entry above) was located on Reedy Creek, between the present Norton Road and Weeroona Drive, and operated between 1871 and 1874. The first teacher was the eccentric, dipsomaniacal Samuel Edmonstone Plumb (1827–?). Having been removed from his role at the school, he served as a private tutor to the children of John Lee (1840–1883) and Thomas Smith (1826–1903). John Lee, referred to below, was a butcher at ‘Creekborough’. The school, where I assume Plumb was still living, was two miles west of the Lake George escarpment.

Plumb had a classical education, and wrote widely. In 1872 he was clearly fascinated by the ground-breaking work of the NSW government surveyors marking the base line of the trigonometrical survey of NSW at the south-eastern part of Lake George. He wrote a long article about it for The Goulburn Herald and Chronicle, concluding with the following ‘familiar gossip’. Note that, in the 19th century, ‘gossip’ meant, among other things, ‘Easy, unrestrained talk or writing, esp. about persons or social incidents’ (OED). Plumb wrote:

I will conclude with a familiar gossip of a special visit I recently paid it [Lake George], in company with one John Lee of these parts. I am in the habit of taking constant rambles to the shores of the Lake ; for, “the pleasure of the pathless wood,” “ the rapture of the lonely shore,” “the society where none intrudes,” can nowhere be so exquisitely enjoyed as on the margin of this water, and its environing hills. John Lee became aware of my small failing for the picturesque; and as he was intimately acquainted with every inch of the ground about the neighbourhood of the Lake, being born and bred in the locality, he most magnanimously offered to cicerone me to an eminence, whence a view of the whole Lake and the southward plains, including the town of Bungendore, could be comprised in a single coup d’oeil. Accordingly, at midday on a certain Sunday, which I hold in fond remembrance, we started for the hill which was to permit us this enchanting view. My dog, Momus a massy fellow, and the companion of my solitary rambles, accompanied us. On the way we passed a hut, and as it is contrary to bush etiquette to go by any habitation without a visit, we were constrained, much against my inclination, to give it a call. We had scarcely entered when the occupier of the hut in adjusting a huge pot of water over a fierce fire, very cleverly upset the whole of the contents over the blazing hearth. The immediate consequence was that the room was filled with the dust and ashes from the fireplace, threatening us with the catastrophe which befell the ancient inhabitants of Herculaneum and Pompeii. We precipitately retreated from the storm of ashes and scoriæ and pursued our journey. Our way lay through a rough and rocky part of the bush, and I was a little in advance of John Lee, when, on surmounting a craggy eminence, I was astonished at the abrupt and magnificent scene, which so unexpectedly burst upon my view. I turned round and looked at John Lee as he came up, and we stood together in silence looking at the fairy scene at our feet, lit up by the dazzling sun overhead. Thus were the man acquainted with books and the man who knew nothing whatever about books, both affected with the same feelings: so true is it that -

One touch of nature makes the whole world kin.